How I Discovered a Dependency Confusion Vulnerability in a Ruby Application Leading to RCE

hey there,

I’m back with another security finding.

Today, I want to share a fascinating dependency confusion vulnerability I discovered, one that led to remote code execution (RCE) .

Grab your coffee, and let’s dive in ☕️

Understanding the Target

As with most bug bounty engagements, everything started with reconnaissance.

I was reviewing one of my targets by:

Browsing their github public repositories

Analyzing their technology stack

Understanding how they managed dependencies

While going through their publicly available code, I noticed that Ruby was one of their primary languages. That immediately made me curious about how Ruby dependencies were handled and whether any internal packages were exposed through misconfiguration...

What Are Ruby Gems Anyway?

For those unfamiliar, Ruby gems are packages or libraries used to share and reuse code. Instead of reinventing the wheel, developers rely on gems for frameworks, utilities, and internal tooling.

There are two types of gems:

Public gems: Hosted on RubyGems.org (anyone can download them)

Private/Internal gems: Hosted on company’s private servers (only employees can access them)

Companies often create internal gems to protect proprietary code, business logic, and internal tools they don’t want to share publicly.

What is Dependency Confusion?

Dependency Confusion (also called a substitution attack) is when a company uses a private package with a specific name, and an attacker registers a public package with the exact same name. The package manager gets confused about which one to install, and if configured incorrectly, it installs the public malicious one instead.

If the attacker publishes a very high version number (for example, 90002.0), many package managers will treat it as the newest version, even if the legitimate internal package exists.

This issue is not Ruby‑specific. It affects npm, pip, Maven, NuGet, and more. Ruby just happened to be my case.

The Classic Attack

In the classic dependency confusion scenario, a company uses multiple gem sources in its Gemfile:

From the first two lines, we can see that Bundler is configured to pull dependencies from two different sources:

rubygems.org(public)internal-gems.company.com(private)

Because internal-gem does not explicitly specify its source, Bundler is allowed to resolve it from either repository ( public and private ).

When developers or CI/CD systems run bundle install, the following happens:

As soon as the gem is installed, malicious code executes automatically.

The correct way to configure this:

With this configuration, Bundler will never look at RubyGems.org for internal-gem.

Why This Is Dangerous

bundle install runs frequently and often automatically:

On developer machines

In CI/CD pipelines

During Docker builds and deployments

Because of this:

Execution requires no user interaction

Both developers and build systems are affected

Production can be reached indirectly through pipelines

This automatic execution is what makes classic dependency confusion vulnerabilities critical.

The Reconnaissance Phase

Now that the risk was clear, I moved into automated reconnaissance.

First, I used ghorg to clone all repositories from the target organization:

Next, I searched for all Gemfile files and extracted gem names:

Finally, identifying which gems were NOT publicly available. I verified each extracted gem against RubyGems:

A 404 means the gem does not exist publicly, signaling a potential target.

While analyzing the target’s projects, I found references to an internal gem that wasn’t available on the public RubyGems.org. This immediately caught my attention.

Building My Proof of Concept

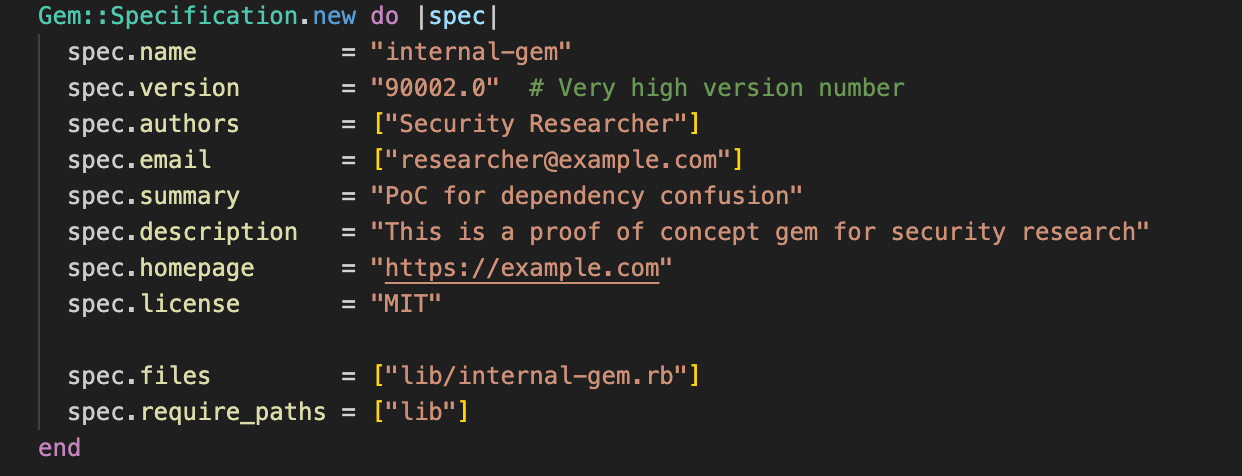

Step 1: Creating the Malicious Gem

I created a gem with the same name as the internal one and set the version to a very high number (90002.0) to ensure it would always be treated as newer

Step 2: Adding the Callback Code

Inside the gem, I added code that executes automatically during installation , Ruby gems can run code at install time without ever being used by the application

The callback was intentionally harmless and only collected:

Hostname

Username

Timestamp

No credentials, source code, or sensitive data were accessed..

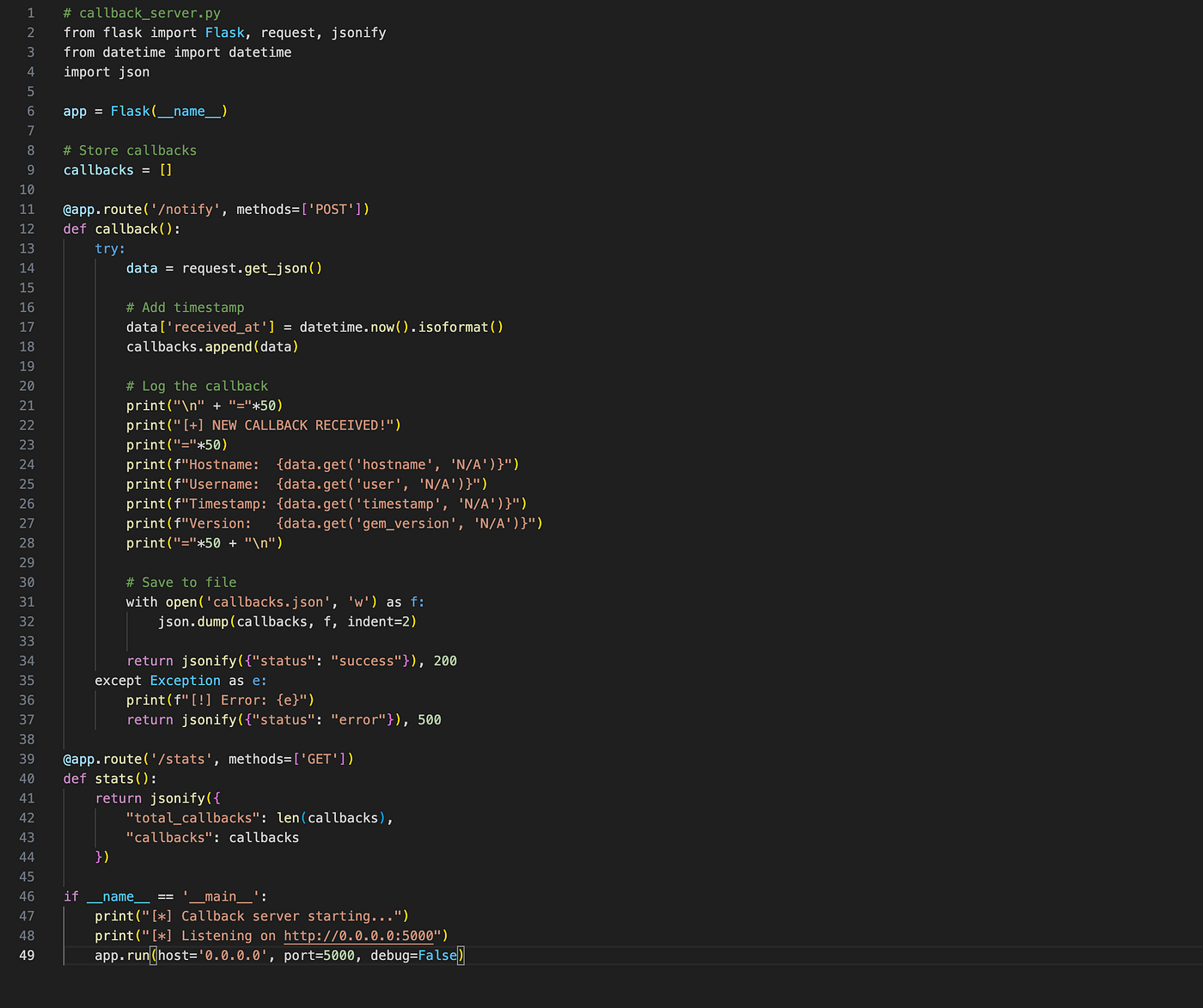

Step 3: Setting Up the Callback Server

Before publishing the gem, I set up a simple web server to catch callbacks. I deployed this to a VPS and made sure it was accessible via HTTPS.

Step 4: Publishing to RubyGems.org

Now came the moment of truth. I published my malicious gem to the public RubyGems repository:

Now my trap was set. I published the gem to RubyGems.org and waited.

The Waiting Game

I started monitoring my callback server:

I left it untouched for several days. Later, I noticed it had received a few requests:

At first, this seemed strange. In a classic dependency confusion scenario, I would normally expect a large number of callbacks, especially if the package was being pulled into CI/CD pipelines or production builds. Instead, the activity was limited

At this point, all I knew was that my malicious gem had been installed somewhere inside their environment.

Now I needed to figure out exactly where this got installed and what that means.

Analyzing The Callback

Let me break down what I learned from that callback:

Hostname:

dev-workstation-xyzThis clearly indicates a development workstation, not production or CI.Username:

engineer_nameA real human user account, not a service user likeci,runner, orbuild.

This wasn’t an isolated case. Other callbacks followed the same pattern:

Hostnames resembling personal workstations

Human usernames

No server‑style naming conventions

No CI/CD or production identifiers

What This Means

The attack only affected individual developer machines, not the entire system.

But why just this one machine? Shouldn’t a dependency confusion attack hit the whole environment? To answer that, we need to look at how Ruby package managers handle gem installations.

Understanding the Attack Vector

Ruby offers two ways to install gems, and the difference matters :

Bundler (bundle install)

bundle install)Bundler is the project-level dependency manager for Ruby. It controls how gems are resolved and installed for a specific application.

At a high level, Bundler:

Reads Gemfile (project-specific dependency list)

Respects source blocks

Checks Gemfile.lock for pinned versions

Installs gems only for the project

Enforces security rules

But: if a gem doesn’t explicitly specify its source, or if a developer bypasses Bundler with

gem install, dependency confusion can still occur.

Gem CLI (gem install)

gem install)The gem command works completely differently:

Ignores your project’s

GemfileUses system-wide gem source configuration instead

Checks all available sources

Picks the highest version number it finds

Installs globally on your machine without project-specific rules

What Actually Happened: Manual Installation

A developer manually ran:

This bypasses Bundler entirely, allowing the public gem with the higher version to be installed.

When you run gem install directly:

This bypasses their security! Even if the Gemfile is configured correctly, those checks only apply when using Bundler (bundle install), not when installing a single gem via the gem command.

Impact

Although production was not affected, a developer workstation often holds highly sensitive access, including:

Source code repositories

Environment variables (API keys, tokens)

SSH keys

Infrastructure and cloud access

Potential for persistence or lateral movement

This makes developer machines a valuable target and a legitimate security concern.

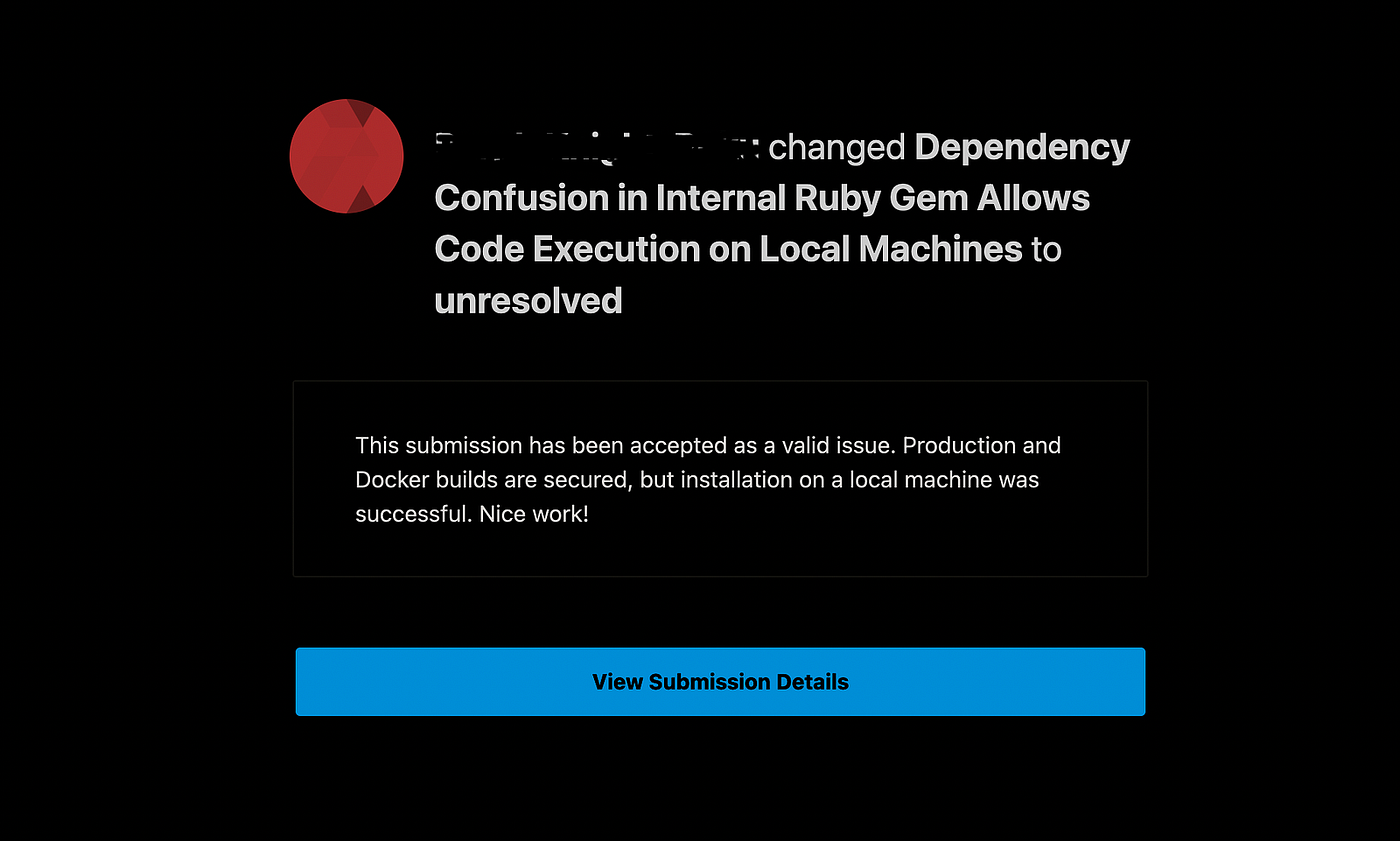

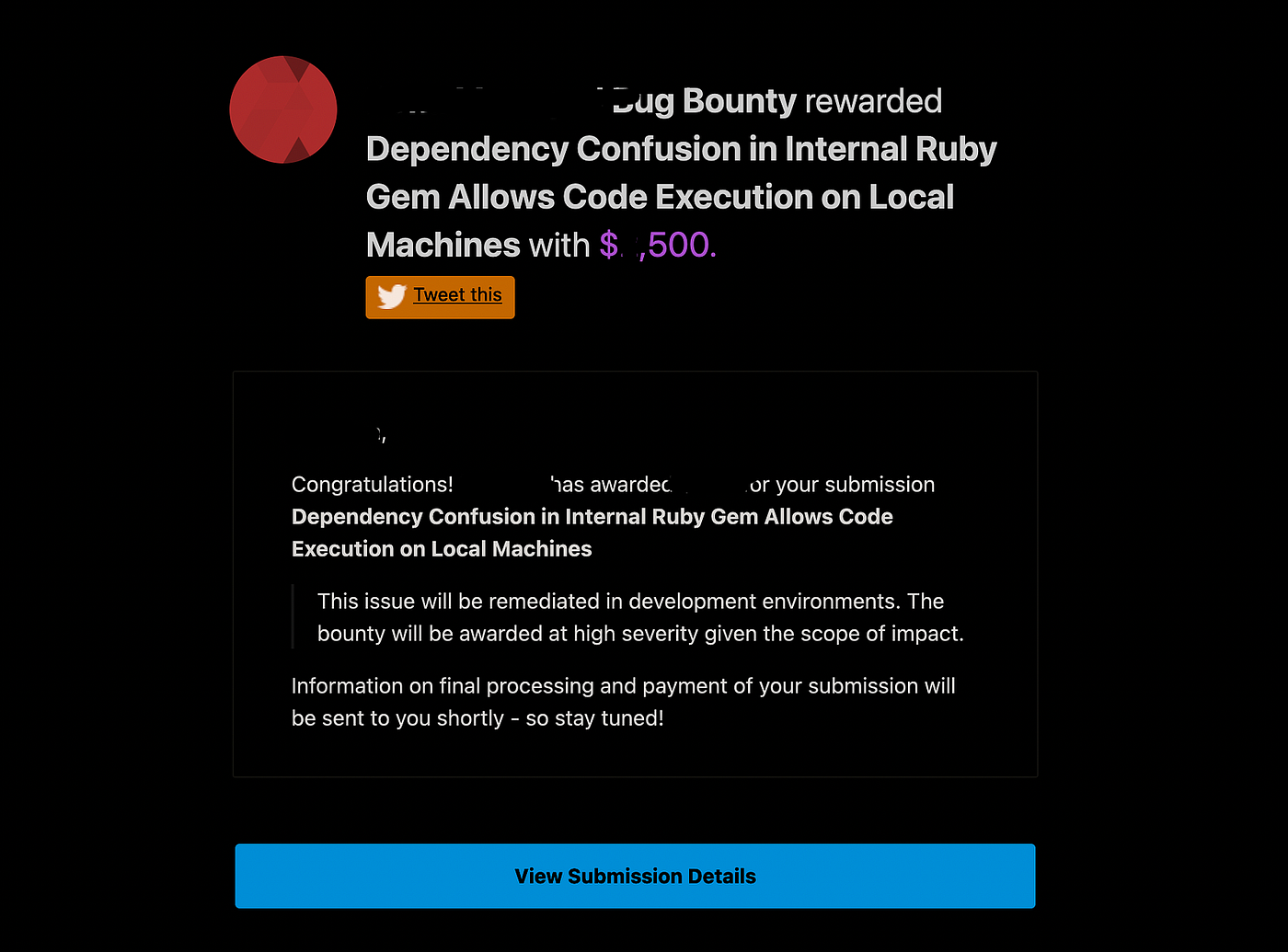

The Company’s Response

I immediately took screenshots of the callback, shut down my server, and submitted a detailed report.

After weeks of discussion, the company confirmed production and CI/CD were secure:

A few hours later, I received confirmation: HIGH severity.

Thanks for reading!

you can follow me on social media to see more Write-Ups and tips

Last updated